Sunderland Point and Samboo's Grave

by Elizabeth Ashworth

Going to Sunderland Point is always a bit scary for me. Just think about the name. Sunder or asunder means apart and when the tide comes in this tiny village which was once a thriving port is now cut off from the mainland at Overton.

Just over a mile of single track road winding over the mud flats and sand marshes connects it to the mainland at low tide. It's hard to imagine that once ships from the West Indies and North America docked here, plying their trade in cotton, sugar and human lives as part of the infamous 18th century slave trade. But there are reminders, and most of the people who come are looking for Sambo's Grave.

Just over a mile of single track road winding over the mud flats and sand marshes connects it to the mainland at low tide. It's hard to imagine that once ships from the West Indies and North America docked here, plying their trade in cotton, sugar and human lives as part of the infamous 18th century slave trade. But there are reminders, and most of the people who come are looking for Sambo's Grave.

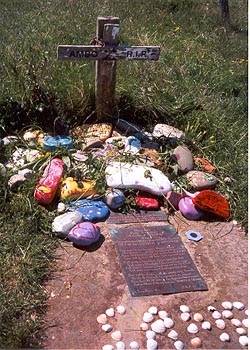

Sambo (or Samboo, as the gravestone indicates) -- I don't suppose anyone knows what his name really was -- was an African and probably no more than a boy. He was a black slave who arrived at the port with his master. He was taken ill, probably with some European disease to which he had no immunity, and he died. Because he was black and not a Christian he was not buried in consecrated ground. His body was interred in land that was once behind the inn, but is now a remote spot on the windswept shore with nothing between him and the vast sea that brought him from his homeland so far away.

For a long time the grave was unmarked, until some years later a retired schoolmaster discovered the story and raised some money for a memorial. He also wrote the epitaph that now marks the grave:

'Full many a Sand-bird chirps upon the Sod

And many a moonlight Elfin round him trips

Full many a Summer's Sunbeam warms the Clod

And many a teeming cloud upon him drips.

But still he sleeps -- till the awakening Sounds

Of the Archangel's Trump now life impart

Then the GREAT JUDGE his approbation founds

Not on man's COLOUR but his worth of heart.'

Sentimental it may be, but its contents show an awareness of changing attitudes towards people from other places.

Now the grave is well visited and fresh flowers have always been laid by people who come from not only curiosity but maybe also a twinge of conscience that such a thing could have happened not just to 'Samboo' but to countless other humans like him.

Don't give up if you can't find it at first. When you reach the hamlet and park your car on the shingle foreshore you must follow a path that leads inland and eventually to the west shore. It is signed but it's easy to miss. The road passes several houses and the small mission church until it narrows to a path almost overpowered by the hedgerows on either side. When I went last time the hawthorn trees were in blossom and the scent was pervasive.

Eventually you will come to a barred metal gate. After going through, turn left and the grave is in a small walled enclave about a couple of hundred yards along the shore. It's always silent except for the calling of the seabirds, and the shoreline is littered with huge sea-bleached trunks of old trees that have been washed ashore on the tide. It gives the place an eerie feeling of isolation. And here lies Samboo, far from his home. He lies in this corner of a foreign field that is forever Africa.

After you've walked back, instead of returning straight to your car, turn right and walk along the eastern shore. There are some lovely houses, probably built by the merchants who once traded here. Look for the row of cottages that used to be a warehouse. For almost two hundred years a 'cotton tree' grew here. But on New Year's Day, 1998 in the fierce storm that did so much other damage down the west coast, the old tree succumbed to the weather and fell. In front of the cottage where it grew is a section of the trunk, the rest of it having been taken away to be analysed. It is thought that the tree was in fact a Kapok tree which is native to the West Indies and could have seeded itself here from some imported matter, or been planted by someone.

Sunderland was built in the eighteenth century by Robert Lawson, a Quaker businessman and there is a story that it was here the first cotton crop to enter Britain arrived. But it lay untouched for two years because no-one knew what to do with it. Perhaps it's a good job that somebody eventually did decide to use it or the cotton towns of the north west would never have evolved.

But as the cotton towns declined, the shifting tides and coastline caused the decline of Sunderland and whilst Glasson Dock and Lancaster can still receive shipping, the port that once overshadowed them is now almost a ghost town. A few people still live there. There is a small post box, a telephone kiosk and a tiny mission church. But it is Samboo's Grave that is the most poignant reminder of what Sunderland once was.

More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Elizabeth Ashworth writes fiction and nonfiction for both adults and children. Her short stories have appeared in such publications as Christian Herald, People's Friend, Take a Break Fiction Feast, My Weekly and Parentcare; her nonfiction has appeared in a variety of magazines, including The Lady, Lancashire Life and My Weekly. She is also a regular contributor to Lancashire Magazine. Her books include Champion Lancastrians (Sigma Press, 2006) and Tales of Old Lancashire (Countryside Books, 2007); she is currently working on a book on Lancashire Graves, and a novel titled "The De Lacy Inheritance."

Article and photo © 2005 Elizabeth Ashworth

|